This manual, developed for Anatomy & Physiology I at UGA, offers a foundational exploration of human anatomy through engaging labs and clinical relevance․

Purpose and Scope of the Manual

This laboratory manual serves as a companion to introductory human anatomy courses, designed for diverse healthcare and science students․ It aims to build a strong foundation in anatomical language, cellular structures, and the comprehensive study of organ systems․

The manual integrates content adapted from multiple open educational resources, with proper attribution provided at each chapter’s conclusion․ Labs cover histology, radiology, and regional anatomy – specifically the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis – fostering both knowledge and practical identification skills․

Target Audience

This manual is specifically tailored for students enrolled in introductory human anatomy and physiology courses․ It caters to a broad spectrum of academic pursuits, including those concentrating in nursing, physical therapy, dental hygiene, and pharmacology․

Furthermore, the content is valuable for students in respiratory therapy, health, physical education, biology, and pre-medical programs․ The labs are designed to provide a practical, hands-on learning experience applicable to various healthcare and scientific careers․

Textbook Transformation & OER Grants

This lab manual’s creation was significantly supported by a Textbook Transformation Grant at the University of Georgia, facilitating its initial development for Anatomy and Physiology I․ Subsequent revisions and enhancements were made possible through a Scaling Up OER Pilot Grant․

These grants enabled the adaptation of multiple open educational resources, ensuring accessibility and affordability for students while maintaining a high standard of educational content and practical laboratory exercises․

Fundamentals of Anatomy

This course establishes a knowledge base in human anatomy, focusing on identifying structures and applying concepts through practical, engaging laboratory activities․

Anatomical Terminology

Understanding anatomical language is crucial for precise communication within the field of human anatomy and physiology․ This section introduces the standardized terminology used to describe body structures, locations, and relationships․ Students will learn directional terms – superior, inferior, anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral – alongside regional terms denoting specific body areas․

Mastery of these terms facilitates accurate observation, dissection, and clinical reporting․ The lab manual emphasizes applying this vocabulary during practical exercises, ensuring a solid foundation for future studies and professional practice․

Body Planes and Sections

Visualizing internal structures requires understanding body planes – sagittal, frontal (coronal), and transverse – which divide the body into specific sections․ This section details how these planes are utilized in anatomical descriptions and imaging techniques․ Students will practice identifying structures based on sectional views, enhancing their spatial reasoning skills․

The lab manual incorporates diagrams and exercises to solidify comprehension of these concepts, preparing students for interpreting medical imaging and performing dissections effectively․

Regional vs․ Systemic Approach

Anatomical study employs two primary approaches: regional and systemic․ The regional approach, utilized in this lab course, focuses on specific body regions – like the thorax or lower limb – examining all structures within that area․ Conversely, a systemic approach studies body systems, such as the skeletal or muscular system, throughout the entire body․

This manual’s regional focus allows for integrated learning, highlighting the interconnectedness of structures within a defined space․

Cellular Level of Organization

This section delves into the cell, the basic structural and functional unit of the body, exploring its components and vital transport mechanisms․

Cell Structure and Function

Cells, the fundamental units of life, exhibit a complex organization crucial for performing specific functions․ This lab explores cellular components like the plasma membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm, detailing their roles in maintaining cellular integrity and activity․

Understanding organelles – mitochondria, ribosomes, and endoplasmic reticulum – is paramount, as they facilitate energy production, protein synthesis, and transport․

Students will investigate how structure dictates function at the cellular level, linking microscopic anatomy to macroscopic physiological processes, forming a strong base for further study․

Cell Transport Mechanisms

Cellular transport is vital for maintaining homeostasis, moving substances across the plasma membrane․ This lab focuses on passive processes – diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion – requiring no energy expenditure․

Active transport mechanisms, like endocytosis and exocytosis, utilizing ATP, will also be examined․

Students will analyze how concentration gradients and membrane permeability influence transport rates, connecting these principles to physiological functions like nutrient absorption and waste removal, building a comprehensive understanding․

Cellular Communication

Cellular communication is fundamental to coordinating bodily functions, enabling cells to respond to their environment․ This lab explores diverse signaling methods, including direct contact, paracrine, endocrine, and synaptic signaling․

Students will investigate how receptors bind to signaling molecules, initiating intracellular cascades․

Emphasis will be placed on understanding the role of communication in maintaining tissue homeostasis and coordinating responses to stimuli, crucial for overall physiological regulation․

Histology: The Study of Tissues

Histology labs examine the microscopic structure of tissues – epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous – revealing their organization and function․

Epithelial Tissue

Epithelial tissue forms coverings and linings throughout the body, exhibiting diverse structures adapted to specific functions․ Laboratory investigations focus on identifying various types of epithelial tissue – squamous, cuboidal, and columnar – based on cell shape and arrangement․

Students will analyze histological slides to differentiate between simple and stratified epithelia, noting the presence or absence of specialized features like cilia or keratin․ Understanding functions of epithelial tissue, including protection, absorption, filtration, excretion, and secretion, is crucial for comprehending organ system physiology․

Types of Epithelial Tissue

Epithelial tissues are classified primarily by both cell shape and the number of cell layers․ Key types include squamous (flat), cuboidal (cube-shaped), and columnar (column-shaped) cells․ These can be arranged in simple (single layer) or stratified (multiple layers) formations․

Labs emphasize recognizing pseudostratified columnar epithelium, often featuring cilia․ Transitional epithelium, found in the urinary system, demonstrates unique stretching capabilities․ Identifying these types under a microscope is fundamental to understanding their specific roles within the body․

Functions of Epithelial Tissue

Epithelial tissues perform vital functions including protection, absorption, filtration, excretion, secretion, and sensory reception․ Their tightly packed cells form protective barriers, like skin, shielding underlying tissues․

Labs explore how specialized epithelial functions relate to location; for example, the absorptive capabilities of intestinal lining cells․ Secretory epithelia, found in glands, produce substances like hormones and enzymes․ Understanding these functions is crucial for comprehending overall body physiology․

Connective Tissue

Connective tissue, a diverse group, supports, connects, and separates different tissues and organs in the body․ Unlike epithelial tissue, it generally has fewer cells and abundant extracellular matrix․

Laboratory exercises focus on identifying various connective tissue types – including connective tissue proper, cartilage, bone, and blood – and correlating their structures with specific functions․ Students will learn how these tissues provide structural support, protection, and transport throughout the body․

Types of Connective Tissue

Connective tissues are broadly categorized into several types, each with unique characteristics․ These include connective tissue proper – like adipose, dense regular, and irregular – providing support and cushioning․ Cartilage, offering flexibility and shock absorption, exists as hyaline, elastic, and fibrocartilage․

Bone provides rigid support, while blood functions in transport․ Laboratory studies emphasize recognizing these types under a microscope, noting cellular arrangements and matrix compositions․

Functions of Connective Tissue

Connective tissues perform diverse functions throughout the body․ They bind structures together, providing support and protection for organs․ Adipose tissue stores energy, while cartilage cushions joints․ Bone offers rigid support and facilitates movement, and blood transports vital substances․

Labs focus on correlating tissue structure with its specific role, emphasizing how matrix composition dictates function․ Understanding these roles is crucial for comprehending overall body physiology․

Muscle Tissue

Muscle tissue is specialized for contraction, enabling movement․ Lab exercises explore the three types: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac․ Skeletal muscle facilitates voluntary movements, while smooth muscle controls involuntary processes in organs․ Cardiac muscle, found only in the heart, pumps blood rhythmically․

Students will examine microscopic structures and relate them to functional properties, understanding how muscle tissue contributes to overall body function․

Types of Muscle Tissue

Skeletal muscle, striated and voluntary, attaches to bones for movement․ Smooth muscle, non-striated and involuntary, lines organ walls for functions like digestion․ Cardiac muscle, found exclusively in the heart, is striated, involuntary, and uniquely branched․

Labs focus on identifying these tissues microscopically, noting key features like striations, nuclei number, and cell shape․ Understanding these distinctions is crucial for comprehending physiological roles․

Nervous Tissue

Nervous tissue specializes in rapid communication via electrical and chemical signals․ The primary cell types are neurons, transmitting impulses, and glial cells, providing support and protection․ Labs emphasize identifying these cells under a microscope, observing neuronal structures like dendrites and axons․

Students will explore glial cell varieties and their specific functions, crucial for understanding nervous system health and disease․

Neurons and Glial Cells

Neurons, the fundamental units of the nervous system, transmit electrical signals․ Labs focus on identifying neuronal components – cell body, dendrites, axon, and synapses – through microscopic observation․ Glial cells, though non-conducting, are vital for neuronal support, insulation (myelin), and immune defense․

Students will differentiate between astrocyte, oligodendrocyte, and microglia, understanding their roles in maintaining neuronal function and overall nervous system health;

The Integumentary System

Labs explore skin structure, including epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, alongside accessory structures like hair follicles and glands for comprehensive understanding․

Skin Structure

The skin, our largest organ, comprises distinct layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis․ Epidermal layers—stratum corneum, lucidum, granulosum, spinosum, and basale—provide protection and contribute to skin tone․ The dermis, containing collagen, elastin, and blood vessels, offers strength and elasticity․

Within the dermis reside sensory receptors, hair follicles, and glands․ The hypodermis, rich in adipose tissue, insulates and cushions․ Labs focus on identifying these structures and understanding their roles in protection, sensation, temperature regulation, and vitamin D synthesis, crucial for overall human physiology․

Accessory Structures of the Skin

Accessory structures – hair follicles, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and nails – enhance skin functionality․ Hair, composed of keratin, provides insulation and protection․ Sebaceous glands secrete sebum, lubricating skin and hair․ Sweat glands regulate temperature through perspiration, with eccrine and apocrine types differing in function․

Nails, also keratinized, protect fingertips․ Laboratory exercises involve identifying these structures microscopically and understanding their roles in maintaining homeostasis and contributing to the integumentary system’s protective and regulatory functions within human anatomy․

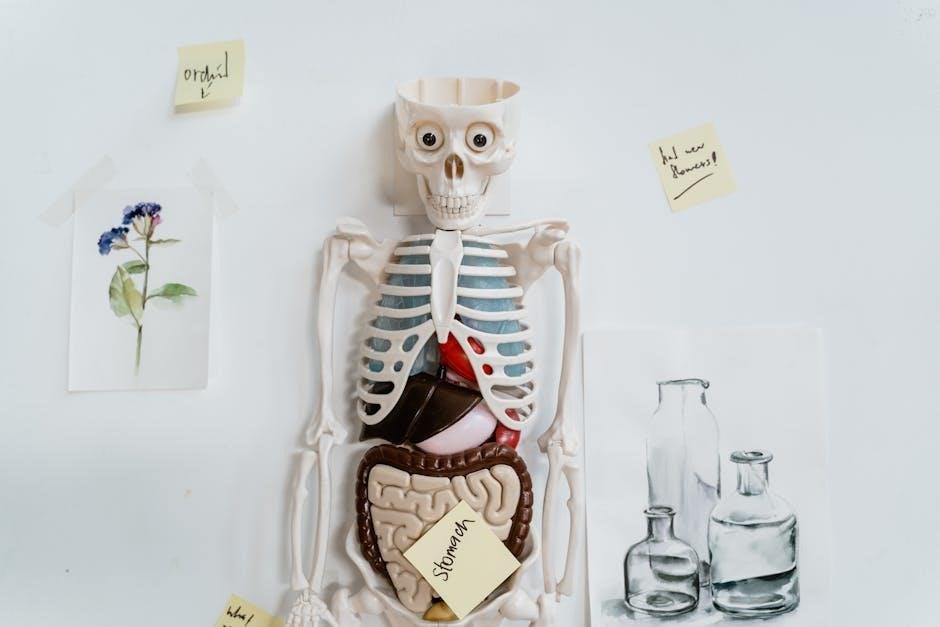

Skeletal System

This section introduces bone classification, structure, and function, providing a basis for understanding the skeletal system’s role in support, protection, and movement․

Bone Classification

Bones are categorized based on their shapes: long, short, flat, irregular, and sesamoid․ Long bones, like the femur, are longer than they are wide and function as levers․ Short bones, such as carpals, are cube-shaped and provide stability․ Flat bones, including the skull, offer protection․

Irregular bones, like vertebrae, have complex shapes․ Sesamoid bones, such as the patella, are embedded in tendons․ Understanding these classifications is crucial for comprehending bone function and anatomical relationships within the skeletal system, aiding in accurate identification and analysis during laboratory exercises․

Bone Structure and Function

Bone exhibits a complex structure comprising compact and spongy bone․ Compact bone provides density and strength, while spongy bone offers lightweight support and houses bone marrow․ Key functions include support, protection of vital organs, facilitating movement via muscle attachment, mineral storage (calcium & phosphate), and blood cell production (hematopoiesis)․

Laboratory study focuses on identifying these structures and understanding how they contribute to overall skeletal function, essential for comprehending physiological processes and clinical applications․

The skeletal system, comprised of bones, cartilage, and ligaments, provides the body’s framework․ This lab introduces its organization, encompassing axial (skull, vertebral column, rib cage) and appendicular (limbs, girdles) divisions․ Students will learn to classify bones – long, short, flat, irregular, and sesamoid – based on shape and function․

Understanding skeletal anatomy is crucial for appreciating movement, protection, and overall physiological support, forming a base for further anatomical study․

Joints

This lab explores joint classifications – fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial – and focuses on synovial joint types, detailing their structure and range of motion․

Joint Classification

Joints are categorized structurally and functionally․ Structurally, they’re classified as fibrous, cartilaginous, or synovial, based on the material connecting the bones․ Fibrous joints, like sutures in the skull, have no joint cavity and are generally immovable․

Cartilaginous joints, such as those in the vertebral column, allow limited movement․ Synovial joints, characterized by a fluid-filled joint cavity, permit a wide range of motion․ Functionally, joints are categorized by their degree of movement: synarthroses (immovable), amphiarthroses (slightly movable), and diarthroses (freely movable)․

Types of Synovial Joints

Synovial joints exhibit diverse structures enabling varied movements․ Plane joints, like intercarpal joints, allow gliding․ Hinge joints, such as the elbow, permit flexion and extension․ Pivot joints, exemplified by the radioulnar joint, enable rotation․

Condylar joints, like the radiocarpal joint, allow angular movements․ Saddle joints, at the carpometacarpal thumb joint, offer greater freedom of movement․ Ball-and-socket joints, such as the shoulder and hip, provide the widest range of motion․

Regional Anatomy: The Lower Limb

This section details the lower limb’s bones, muscles, and nerves, providing a regional study of anatomical structures and their functional relationships․

Bones of the Lower Limb

The lower limb’s skeletal framework comprises several key bones essential for weight-bearing, locomotion, and stability․ This includes the femur, the longest and strongest bone in the human body, articulating with the pelvis at the hip joint․

Distally, the femur connects to the tibia and fibula at the knee․ The tibia, the larger weight-bearing bone, and the fibula, providing lateral stability, extend to the ankle․

Finally, the foot consists of tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges, enabling propulsion and balance․ Understanding the individual bone structures and their articulations is crucial for comprehending lower limb function․

Muscles of the Lower Limb

The lower limb’s muscular system is a complex network responsible for a wide range of movements, from walking and running to jumping and maintaining posture․ Major muscle groups include the gluteals (hip extension), hamstrings (knee flexion and hip extension), and quadriceps (knee extension)․

Anterior compartment muscles primarily dorsiflex the foot, while posterior compartment muscles plantarflex it․ Leg muscles also contribute to inversion and eversion․

Understanding muscle origins, insertions, and actions is vital for analyzing lower limb biomechanics and clinical conditions․

Nerves of the Lower Limb

The lower limb’s nerve supply originates from the lumbar and sacral plexuses, branching into major nerves like the femoral, obturator, and sciatic nerves․ The femoral nerve innervates the anterior thigh, while the obturator nerve serves the adductor muscles․

The sciatic nerve, the largest in the body, divides into the tibial and common fibular (peroneal) nerves, controlling the posterior thigh, leg, and foot․

These nerves transmit motor commands and sensory information, crucial for lower limb function and sensation․

Regional Anatomy: The Upper Limb

This section details the upper limb’s bones and muscles, providing a comprehensive study of its structure and function for practical application․

Bones of the Upper Limb

The upper limb’s skeletal framework comprises the humerus, radius, and ulna, forming the arm and forearm respectively․ Distally, the carpals constitute the wrist, articulating with the metacarpals of the hand, and finally, the phalanges of the fingers․

Laboratory exercises will focus on identifying these bones, their key landmarks, and articulating surfaces․ Students will explore bone classifications and understand how their unique structures contribute to the limb’s range of motion and functionality․

Practical application involves correlating bony landmarks with surface anatomy, aiding in clinical assessments and understanding potential injury sites․

Muscles of the Upper Limb

The upper limb’s muscular system is a complex network responsible for a wide range of movements․ Key muscle groups include those of the shoulder (deltoid, rotator cuff), arm (biceps brachii, triceps brachii), and forearm (flexors and extensors)․

Lab sessions will emphasize muscle origin, insertion, action, and innervation․ Students will learn to identify muscles palpatorily and correlate their function with specific movements․

Clinical relevance will be explored through case studies examining muscle strains, tendonitis, and nerve injuries affecting upper limb function․